Stećci–Medieval Tombstones Graveyards were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List on July 15 2016.

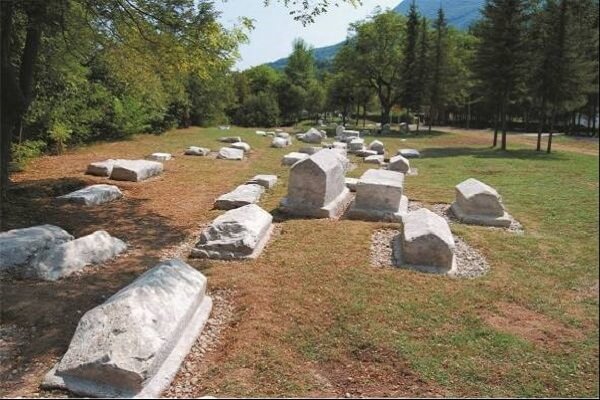

This serial property includes a selection of 4000 medieval tombstones (stećci) at 28 sites on the territory of four states: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republic of Croatia, Montenegro, and Republic of Serbia. Stećci bear an exceptional testimony to the medieval culture of Southeast Europe that was developed within a unique historical context in an area where traditions and influences of the European West, East and South meet.

There are several fundamental characteristics that distinguish stećci from the overall corpus of the European, and the world’s, medieval heritage and sepulchral art: a large number of preserved monuments (over 70,000), the diversity of forms in which they were hewed, the richness of decorative reliefs, epigraphy, multi-confessionality and wealth of intangible heritage related to stećci.

Recognizing their Outstanding Universal Value, the World Heritage Committee has designated Stećci–Medieval Tombstones Graveyards as a World Heritage site.

Stećci are medieval monolithic tombstones found on the territory of almost entire Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the western parts of Serbia and Montenegro and in central and southern parts of Croatia. The zone of outspread of stećci is limited to the north by the Sava River, the Adriatic coast to the south, Lika in Croatia to the west while the eastern boundary of their outspread reaches deep into western Serbia.

There are around 70 000 registered tombstones at about 3 300 sites on the territory of the mentioned states. However, since the inscription of stećci on the World Heritage List in 2016, we know that there may be a larger number of these monuments and sites.

It is assumed stećci first appeared in the second half of the 12th century and they were most intensively hewed in the 14th and 15th century, before gradually ceasing to be made in the 16th century. Certain forms (slabs, crosses) and decorative motives were being created for a much longer period, but it was no longer the classic “art of stećci.”

There are several names that were used in parallel to denote the tombstones (stećci), which shows a close bond of folk life with the tradition of stećci. The first type are expressions that rely on authentic historical sources – mostly inscriptions on stećci: bilig (mark), kâm (stone), zlamen (sign), kuća (house) and vječni dom (eternal abode). The popular names that took root among people include Mramorje, Mramori (marble blocks), Grčko groblje (Greek cemetery), Kaursko groblje (giaour cemetery), Divsko groblje (giants’ cemetery) and Mašet or Mašete – (big stones). Today’s name stećak first appeared in mid-19th century and is derived from the verb ‘standing’.

Stećci were mostly made of limestone – a most common type of stone in this region very suitable for carving. In the areas where there was no limestone, stećci were hewed from serpentine, slate, conglomerate, tuff and other types of stone. The stones for stećci were quarried mainly in the vicinity of cemeteries bearing in mind that those were stone blocks of up to several tons. The cemeteries with stećci were mostly formed as ‘cemeteries in rows’, as was the custom in European funerary practice which lasted since the early Middle Ages and the time of the so called Great Migrations, and one stećak could have been used to mark one grave or several graves.

According to the shapes of stećci they are divided into five basic types with variations: slab, chest, sljemenjak (gabled roof stećak), križina – monumental cross, and pillar. The largest number of stećci belongs to the group of chests and slabs. Sljemenaci, even though less numerous than the previous forms, are the most recognizable form of stećci that emerged during their “classical” phase throughout the 15th century. Monumental crosses and pillars, which have also been preserved in smaller numbers, belong to the last stage in the development of stećci at the end of the 15th and early 16th century. In addition, there are two more shapes which, in terms of their placement and decorations, may only be partially included into stećci. These are steles and nišani which also emerged at the end of the “era of stećci.”

Stećci bear an exceptional testimony to the medieval culture of Southeast Europe that was developed within a unique historical context in an area where medieval cultures and traditions of the European West, East and South meet. In addition, in some respects, stećci also drew influences from much earlier – prehistoric, ancient and early medieval, traditions. As much as they are associated with the general medieval sepulchral practice, it is the multitude and monumentality but also the interconfessionality of stećci as elements of cultural heritage that make this region stand out from the overall corpus of the medieval European heritage.

Decorative Motives and Epitaphs

Among the decorative motives on stećci with their emphasized symbolism typical of medieval art, there are secular and religious symbols and other ornaments intertwining and integrating medieval reality in ancient and prehistoric traditions.

Decorative motives may be divided into: social and religious symbols (different types of crosses, tools, weapons, new moon, stars, anthropomorphic lilies, solar motifs, etc.), figural compositions (images of men and women, jousting scenes, tournaments, hunting, parades of people, so-called funeral wheel-dances – kolo- and images of animals) and numerous vegetal and geometric ornaments.

Epitaphs on stećci are an unmistakable indicator of cultural diversity of this region, especially when in the same territory and at the same time, various cultures and spiritual patterns touch on and permeate one another.

The epitaph in fact established a two-way communication: a message sent to the deceased for the peace of his soul and a message from the deceased for religious education of the living.

Viewed in the broadest temporal and spatial as well as historical context, the inscriptions on stećci represent an organic part of Christian epigraphic culture of medieval Europe and its development phases between the 14th and 15th century. Many preserved inscriptions, mainly in Bosnia and Herzegovina and to a lesser extent in Croatia, Serbia, and Montenegro, reveal that stećci were unique monuments of medieval literacy ranging from royal and high-nobility offices and monastic scriptoria to the lower, more or less noble strata of society. The language and script are exclusively local and the inscriptions were regularly written in Cyrillic, while the contents are indeed different and may be divided into two main groups: inscriptions with religious and those with secular contents (which may be subdivided into smaller groups depending on the size and content.

The prevalence of the shtokavian ikavian dialect in these texts indicates a single language and literacy of the 14th and 15th century (and later) on a relatively large territory, the language in which the texts of contemporary secular documents were written (charters, wills, contracts and diplomatic material in general) as well as church books (primarily preserved missals and gospels).

Stećci represent a genuine artistic expression created in specific circumstances of intertwining of various cultural influences.

By diversity of types, abundance, richness of decorative motives, the occurrence of inscriptions of different content, the context of their creation, stećci remain a unique phenomenon in medieval European artistic and archaeological heritage.